In the last week or so my background viewing over meals and housework has been a Let’s Play of FromSoftware’s Bloodborne, a gothic horror fantasy spiritually succeeding the same developer’s infamously difficult Souls

series. I’m not likely to ever play it myself, although I’d be interested to see somebody with different play habits and strategies attempt it. These days I’m getting more set in what interests me and Bloodborne

, while interesting in some ways, offers me more as a spectacle than as a game.

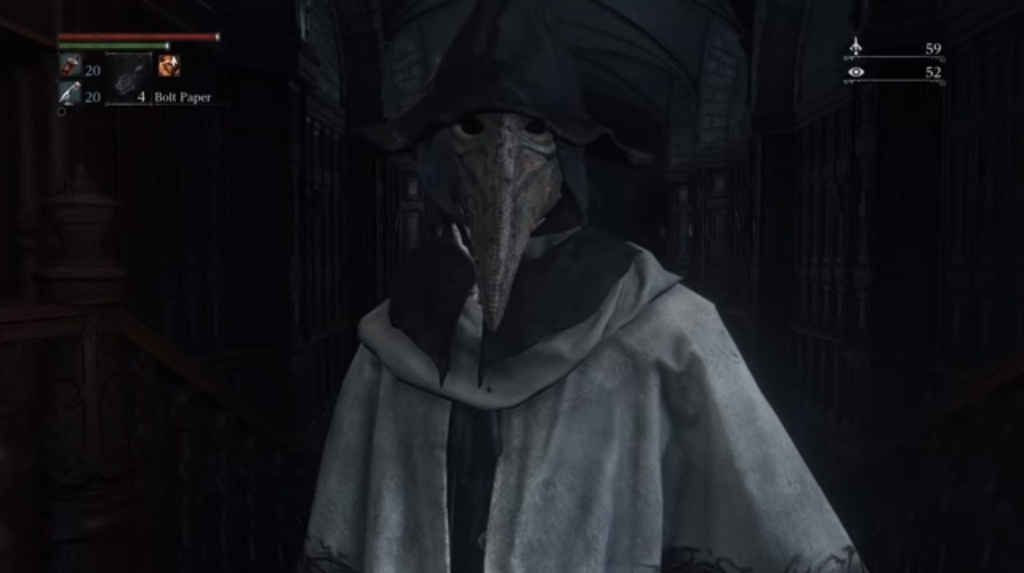

Anyway, as a spectacle, Bloodborne is ugly. In the tradition of gothic fiction, it’s supposed to be ugly. It’s supposed to be dark, leather-clad and wet with blood. Unlike the medieval apocalyptic fantasy in the Souls

series, Bloodborne

is urban and industrial. Working class cockney accents howl, cackle and plead in the backdrop of the mute protagonist’s bloody romp through Victorian

London Yarnham. Although Bloodborne has a fairly complex mythology and plot, virtually none of it is told directly. In fact, while it follows gothic horror tropes quite strictly, they’re communicated almost exclusively through visual and ludic languages.

There’s this whole business of a city discovering and adopting a bold new power—blood, naturally—that sparks rapid progress at the cost of summoning monsters and transforming citizens into an unruly mob of lunatics (the game takes place in a gradually darker and more supernatural night). Not unlike gothic horror, the fixation on blood and viscera is not just a medical curiosity. The dangers of exploring and mobilizing blood as a fuel for progress meshes with the historical use of coal that blackens the sky, crowds cities and stratifies a pompous, cruel aristo-capitalist class against a filthy, angry and mistrusted labouring and peasant class. Mud and slimy tentacles are everywhere. Yarnham is not a nice place to live and, naturally, brings out the worst in people. Think Poe, Lovecraft, Wells, whatevs. Of the few people remaining that aren’t actively hostile, all are suspicious and unhinged.

Many RPGs have a cynical, capitalistic undertone to their heroic gestures where altruism is rewarded with stuff. But this works in Bloodborne because the patients run the asylum, as it were, and everybody is out for themselves. All are monsters among monsters. It’s the kind of omnipresent hostility and mistrust that was supposed to permeate Bioshock

but never really stuck given its vision of morality is so binary.

Every setting in Bloodborne is touched by human hands: even the depths of twisted forests and rocky deserts have cobblestone paths and grotesque statures lining the periphery. That’s the point. In Yarnham, there is nothing that hasn’t been meddled with the de-naturizing power of blood (coal) and the air, earth and water have been tainted by the meddling hands of an arrogant upper class and an ignorant lower class. Yarnham is a nightmare of industrialization caked in blood and shit. Even hunters like the player-character, tasked with destroying the beasts prowling the city, are empowered by blood and often doomed to succumb to its temptations. Cthulhu rises from the ocean, unaware and unconcerned with the filthy human insects below it; we stand in awe and terror in the face of our own meaninglessness, building our pyramids and cities as ants scrounging together a nest and yadda, yadda, yadda. The most nihilistic ending is the one the player must work hardest to earn. Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

But Bloodborne‘s particular inflection on gothic horror and Victorian cynicism, for me, is in the way that the player’s avatar moves. Unlike the (somewhat) aesthetically similar Assassin’s Creed

, there is no sense of freedom in motion. Having not played it, I can’t really speak to the kinaesthetics of moving in Bloodborne

‘s world, but even confrontations with bosses are cramped and spotted with pillars and garbage in the way. The space makes for generally poor battle arenas. Stairways, alleys and bridges flow awkwardly in tight, inconvenient and suffocating spaces. Again, I think this works for the game because the urban space is more a sprawl of patchwork paths leading from one area to the next than an effort to provide would-be citizens with public social space. Much of the space doesn’t seem like it’s very good to fight in, and one can imagine that it would not be a very good place to hang out in even if everybody weren’t out to kill you. Spatially, Yarnham is a series of winding paths dragging the player through tenuously connected districts in a way not too unlike an early industrial city is a confusing mess of streets and corridors leading workers to the factory and back. The kind of urban space designed to crystallize class barriers with streets and bridges. You are compelled to know where you stand based on where you literally stand.

Yes, Yarnham is a digital city and its urban planners are more interested in a single person’s experience than in a society’s, but I’m fascinated by how much of the city’s identity hinges on the restriction of mobility. Restricted motion is clearest, to me, in how the player-character fights. Most of the player’s melee weapons have two forms: one where they fight with a one-handed weapon in one hand and a firearm in the other; the second form of most melee weapons is a larger, more cumbersome but deadlier two-handed version. In both of these modes, movement is stilted and inelegant. When either the PC or the beasts swing their weapons they look like they’re hurting themselves as much as their opponent. Attacks are heavy and frenetic, wailing on an opponent with a heavy brick or hammer or firing a flintlock pistol at point-blank into someone’s face isn’t stylish and it certainly isn’t ergonomic. The tools of the hunter’s trade put major stress on their bones and joints.

Where fiction has no shortage of impractically large weapons, in Monster Hunter or Valkyrie Profile

movement emphasizes the wielder’s power: we aren’t supposed to wonder how an anime character can swing such a heavy sword with such grace because a part of the fantasy is that a superhuman body is capable of doing with ease what we know our own bodies can’t. But swinging giant swords in Bloodborne

or watching massive wolf creatures smash their claws into stone looks like it really hurts. The avatars twist just a little too much, tilt a little too far with the momentum of their swing. It looks like it would cause considerable back pain! The fact that the player character keeps coming back to life and pulling their spine out of joint throughout an endless night seems every bit a part of the curse as the trolls and gargoyles.

More than that, the actual movement of combat speaks to the unifying quality of industrialism on the human body. Once again, it’s an uncomfortable unity. Hunters and monsters aren’t just made one by the exaggerated weight of fighting, but their fighting shares the same rhythm. The player steps back and forth in patterns of tense evasions and heightened aggression and vulnerability. Both the player and their foe hurl forward in turns, attacking in a frenzy when a weakness opens up and wheeling back to desperately shake the reprisal. The motions continue until one or the other is mashed into the brickwork. The PC is not really the hero here, rather just another monster: not only does the PC’s use of blood suggest as much but, tactically, they resemble most of the game’s enemies. The PC charges forward violently and, in exchange, becomes imperiled when they spend the last of their stamina on the attack. The choreography of the PC matches that of the beasts they fight.

The hyper-stylized dashing, flipping and posing in Devil May Cry or Bayonetta

has no place in Bloodborne

; but neither does the trepidatious inching around corners of Resident Evil

or Amnesia

. When the PC takes damage, they may restore their health by immediately counterattacking and drawing blood from a nearby enemy. So the dance maintains a constant aggression: dodging and rolling out of harm’s way is only so effective. The ebb and flow of combat maintains the cynicism of Bloodborne

‘s genre and setting. The solution to dehumanized industrial progress is more progress, which further dehumanizes. Providing for a more complex public means controlling the mobility of the public. The annihilation of monsters requires becoming a monster. Victory against hideous aggression is to aggress hideously.

Although Bloodborne isn’t the game for me, I’m glad I was able to experience it vicariously because its aesthetics really speak to a certain vision of the world. Not even one that I necessarily hold, but one I find powerful nonetheless. While I can’t be arsed to master it myself, it manages to speak to a genre’s ontology almost entirely—and most effectively—with the aesthetics of movement in a distinct environment. I dig that.

Further reading: McMullan, Thomas. “From Dark Souls to Manifold Garden: How games tell stories through architecture.” Aphr. Mar

English, Phill. “Palette Swap: ‘Colour Balance’.” Tim and Phill Talk About Games. Apr 28 2016.

Bee, Aevee. “Bloodborne: The Authentic European Hellscape Vacation.” Gaming Intelligence Agency. Apr 6 2015.

Blue, Lulu. “The 3-System Structure.” Erogazmo. Apr 5 2015.

Fantastic article. The DLC further confirms your claim about the corruption of nature by the upper class elites of Yharnam. I never thought about the physicality with swinging the weapons. Very interesting

Interesting analysis on the physicality of the characters in Bloodborne. I’ll say that the movements and combat in it have a higher degree of smoothness and that combat is more frenetic than in Dark Souls 1 and 2. Activity in Bloodborne, however, does seem a strain to many of the characters, which, along with being covered in blood, might be that games visual depiction of the stress and degradation brought on by the activity of being a hunter. Dark Souls 1 and 2 have their hollowing mechanic, showing the player the results of existing in that setting as well as a reminder of the death(s) they incurred (Demon’s Soul phantom form is more mechanically intrusive than visually).

Thanks for this unique take on the game.